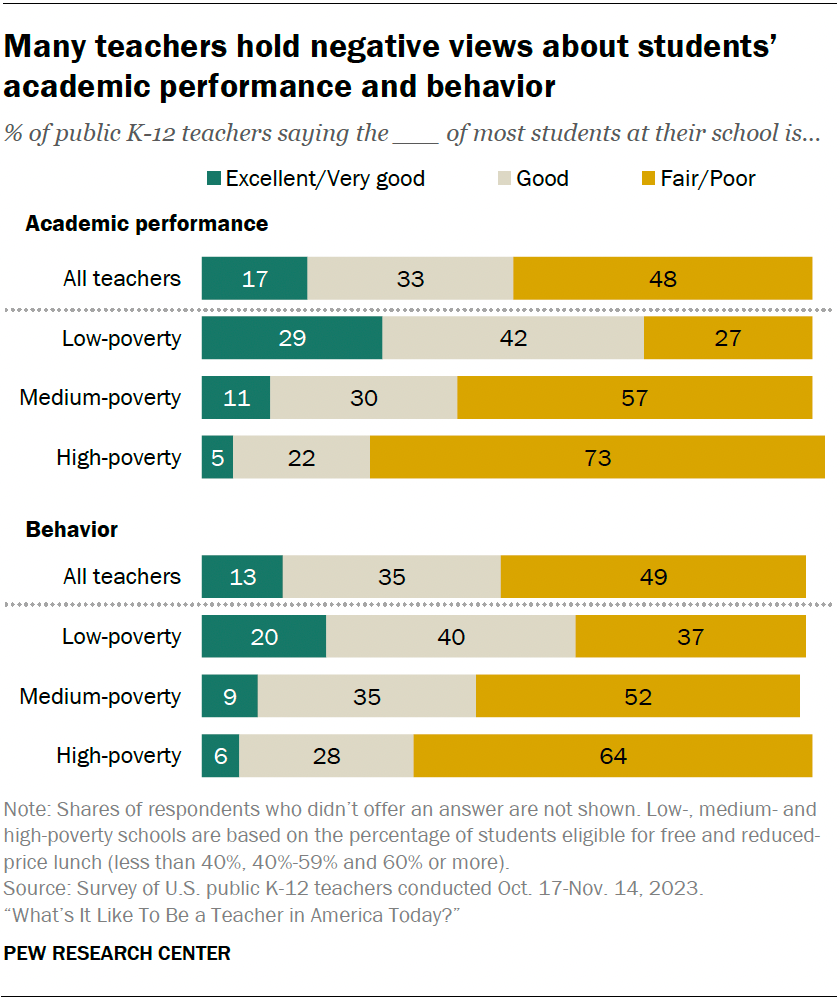

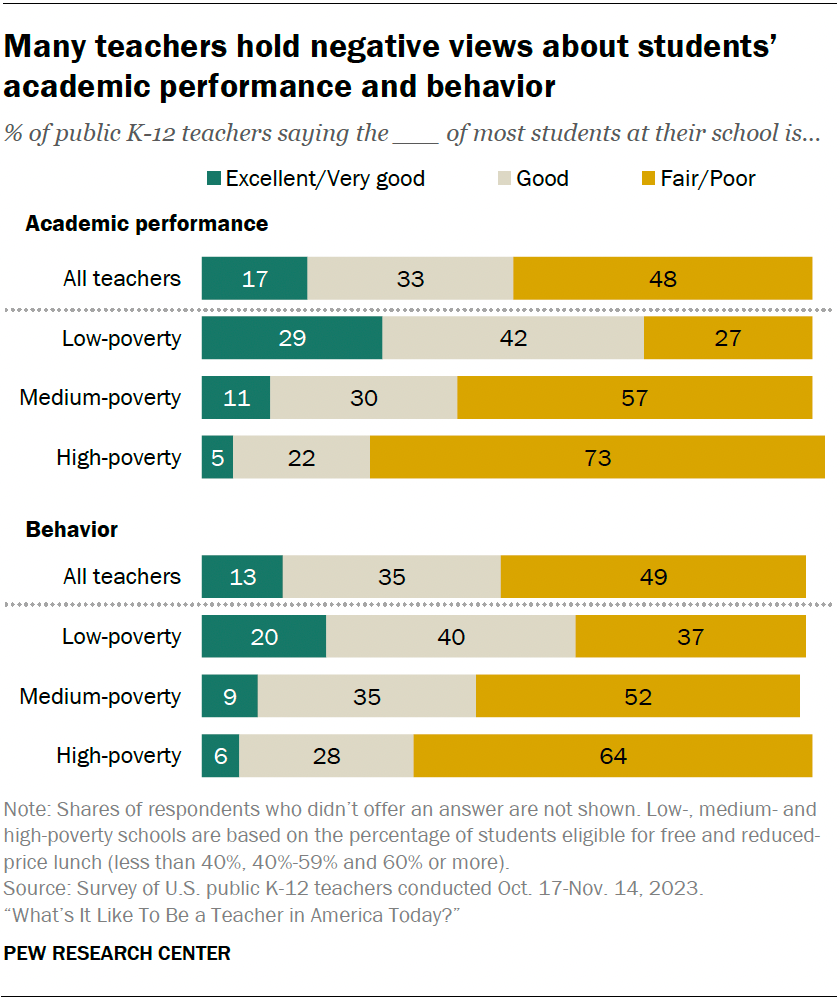

We asked teachers about how students are doing at their school. Overall, many teachers hold negative views about students’ academic performance and behavior.

Teachers in elementary, middle and high schools give similar answers when asked about students’ academic performance. But when it comes to students’ behavior, elementary and middle school teachers are more likely than high school teachers to say it’s fair or poor (51% and 54%, respectively, vs. 43%).

Teachers from high-poverty schools are more likely than those in medium- and low-poverty schools to say the academic performance and behavior of most students at their school are fair or poor.

The differences between high- and low-poverty schools are particularly striking. Most teachers from high-poverty schools say the academic performance (73%) and behavior (64%) of most students at their school are fair or poor. Much smaller shares of teachers from low-poverty schools say the same (27% for academic performance and 37% for behavior).

In turn, teachers from low-poverty schools are far more likely than those from high-poverty schools to say the academic performance and behavior of most students at their school are excellent or very good.

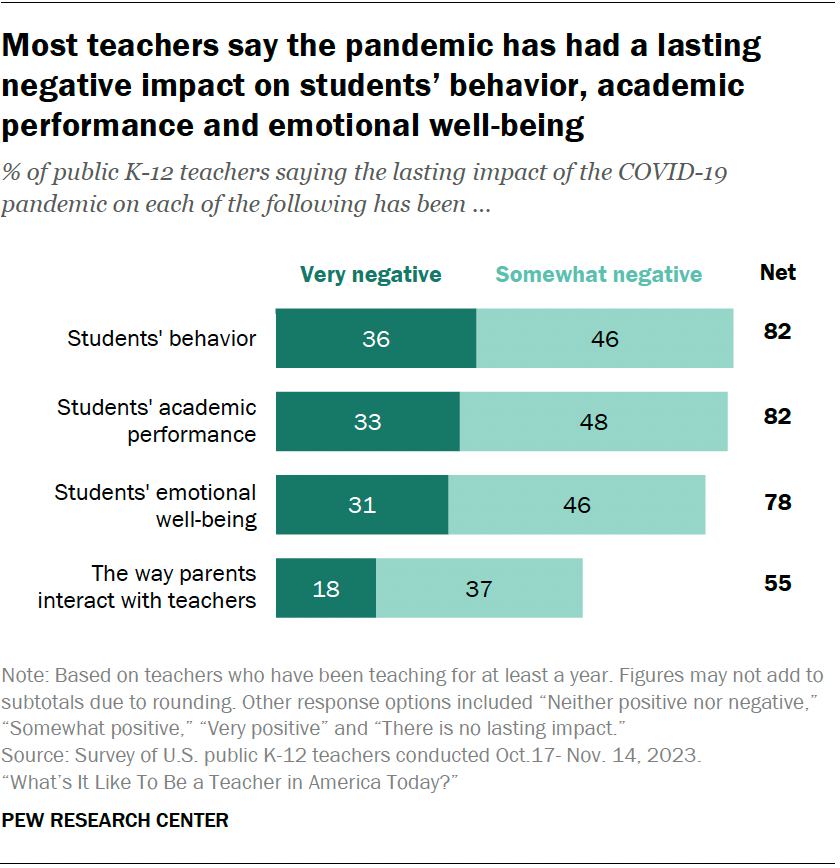

Among those who have been teaching for at least a year, about eight-in-ten teachers say the lasting impact of the pandemic on students’ behavior, academic performance and emotional well-being has been very or somewhat negative. This includes about a third or more saying that the lasting impact has been very negative in each area.

Shares ranging from 11% to 15% of teachers say the pandemic has had no lasting impact on these aspects of students’ lives, or that the impact has been neither positive nor negative. Only about 5% say that the pandemic has had a positive lasting impact on these things.

A smaller majority of teachers (55%) say the pandemic has had a negative impact on the way parents interact with teachers, with 18% saying its lasting impact has been very negative.

These results are mostly consistent across teachers of different grade levels and school poverty levels.

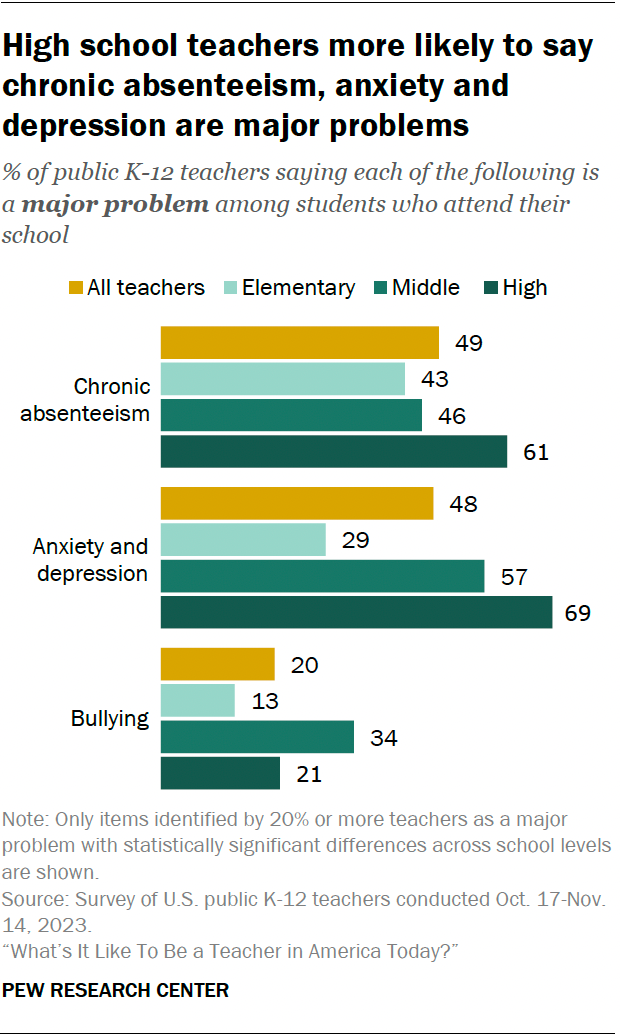

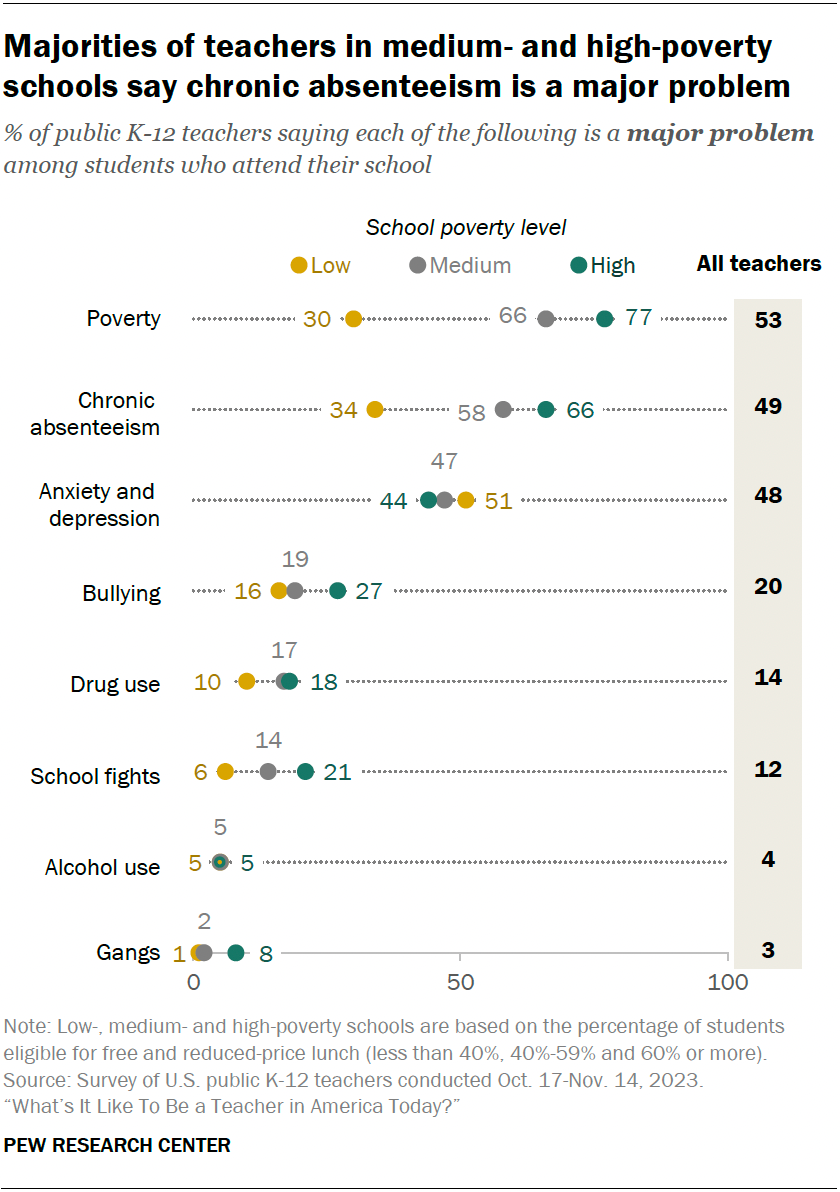

When we asked teachers about a range of problems that may affect students who attend their school, the following issues top the list:

One-in-five say bullying is a major problem among students at their school. Smaller shares of teachers point to drug use (14%), school fights (12%), alcohol use (4%) and gangs (3%).

Similar shares of teachers across grade levels say poverty is a major problem at their school, but other problems are more common in middle or high schools:

Not surprisingly, drug use, school fights, alcohol use and gangs are more likely to be viewed as major problems by secondary school teachers than by those teaching in elementary schools.

Teachers’ views on problems students face at their school also vary by school poverty level.

Majorities of teachers in high- and medium-poverty schools say chronic absenteeism is a major problem where they teach (66% and 58%, respectively). A much smaller share of teachers in low-poverty schools say this (34%).

Bullying, school fights and gangs are viewed as major problems by larger shares of teachers in high-poverty schools than in medium- and low-poverty schools.

When it comes to anxiety and depression, a slightly larger share of teachers in low-poverty schools (51%) than in high-poverty schools (44%) say these are a major problem among students where they teach.

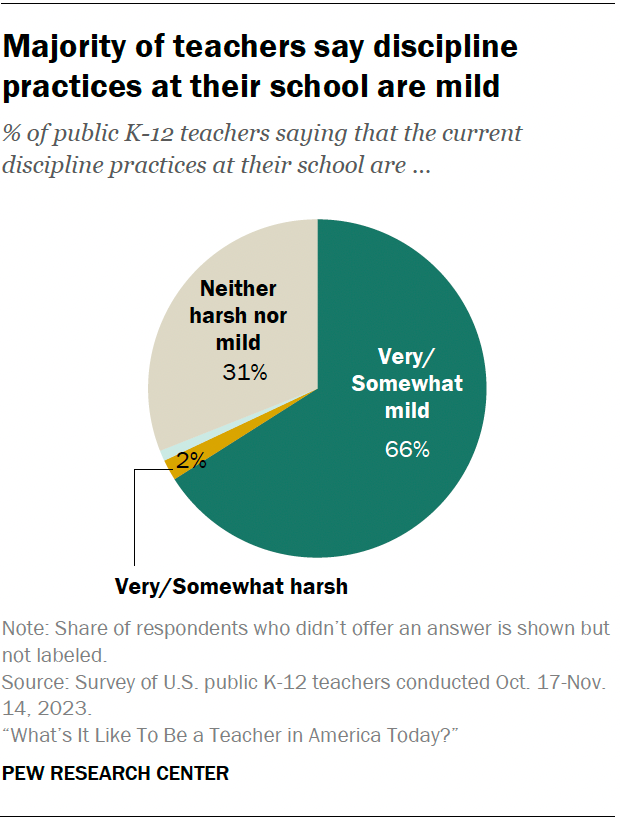

About two-thirds of teachers (66%) say that the current discipline practices at their school are very or somewhat mild – including 27% who say they’re very mild. Only 2% say the discipline practices at their school are very or somewhat harsh, while 31% say they are neither harsh nor mild.

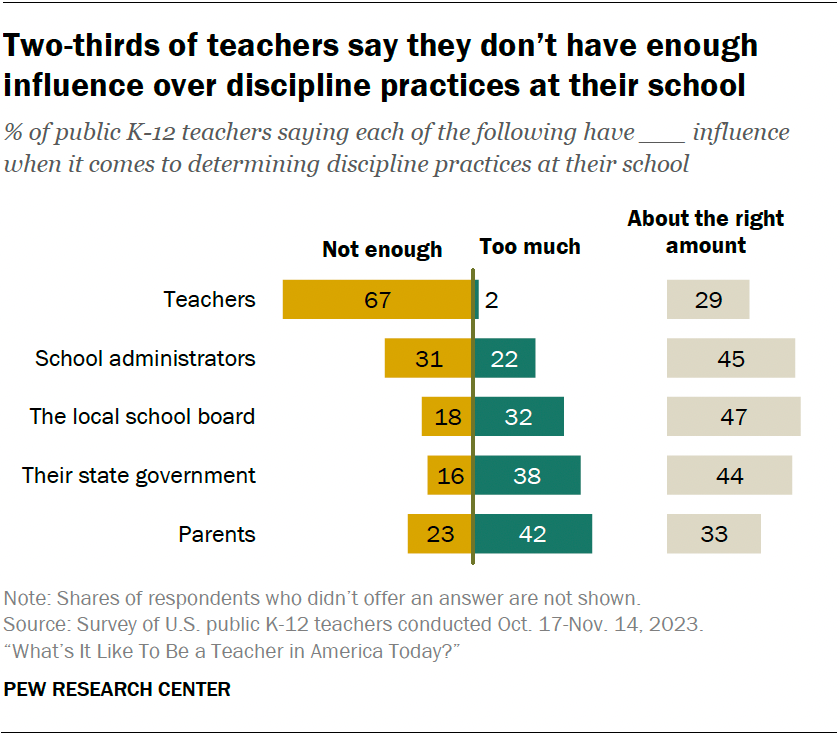

We also asked teachers about the amount of influence different groups have when it comes to determining discipline practices at their school.

Teachers from low- and medium-poverty schools (46% each) are more likely than those in high-poverty schools (36%) to say parents have too much influence over discipline practices.

In turn, teachers from high-poverty schools (34%) are more likely than those from low- and medium-poverty schools (17% and 18%, respectively) to say that parents don’t have enough influence.